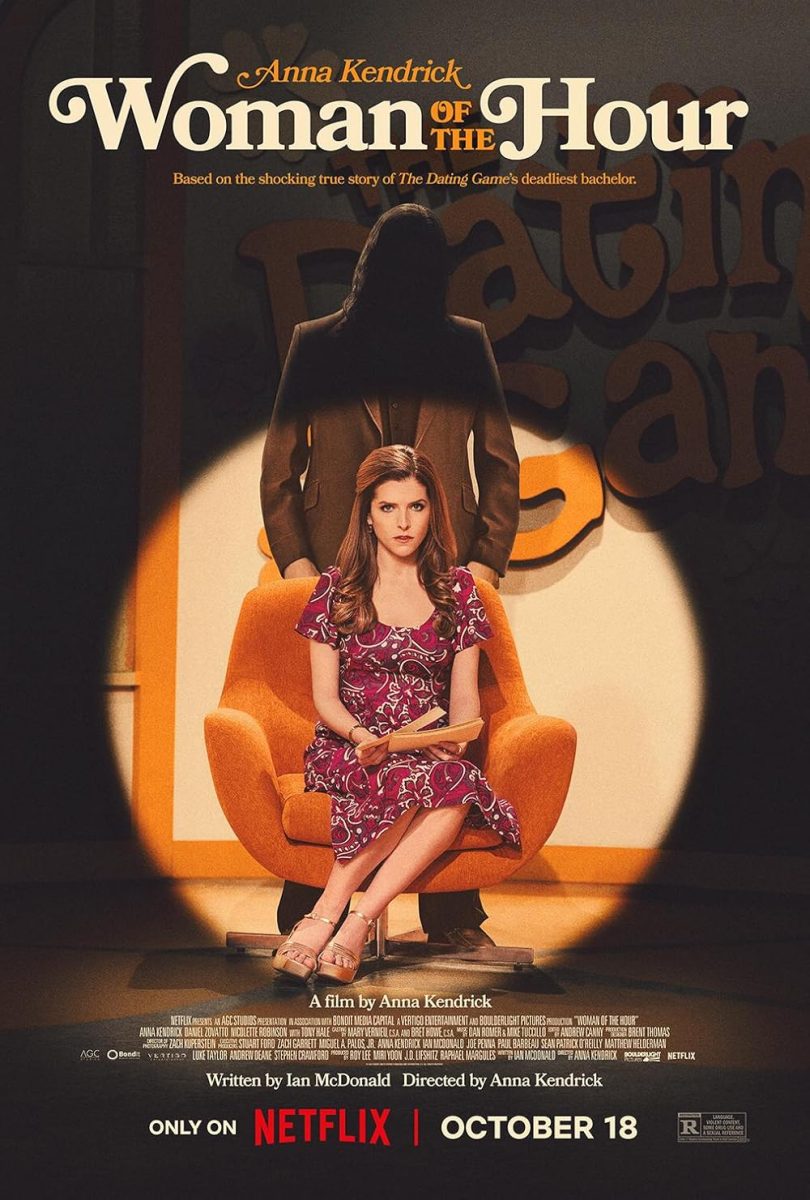

Anna Kendrick’s “Woman of the Hour” boldly interrogates the exploitation of women and the intersections of misogyny and violence in a dramatization of the true-crime story of Rodney Alcala, the serial killer who appeared on the TV show “The Dating Game.” Kendrick, in her directorial debut, crafts a narrative that critiques not only the violence of Alcala’s crimes but also the systems and cultural attitudes that allowed his public persona to overshadow his reality.

The film contrasts two parallel narratives: Cheryl Bradshaw (played by Kendrick), a contestant who unknowingly selects Alcala as her date on the game show, and Alcala himself (Daniel Zovatto). Adding a third dimension to the story is the character, Laura (Nicolette Robinson), a young woman whose friend was brutally murdered by Alcala. Her attempts to alert authorities to his suspicious behavior are left unheard, reflecting a system unwilling to take women’s voices seriously.

Cheryl Bradshaw is a young actress in California during the 1970s, struggling to make a name for herself in an industry that often chews women up and spits them out. As the film begins, Cheryl is at her breaking point, frustrated by dead-end auditions. Just as she’s considering leaving her acting career behind, her agent calls with a new opportunity: a chance to appear on a popular reality dating show. Believing this could be her big break, Cheryl reluctantly agrees, hoping to use the spotlight to further her career.

On the set of “The Dating Game,” Cheryl finds herself caught up in the artificiality and performative charm of the show. As the lights blaze and the audience cheers, she interacts with three unseen bachelors, ultimately choosing Alcala based on his witty, albeit unsettling, answers. While Cheryl expresses unease almost immediately after meeting him in person, the show’s producers dismiss her concerns, encouraging her to fulfill her role as a good sport. Her refusal to go on the date with Alcala is framed as a moment of agency, yet it also shows society’s failure to hear women’s voices, leaving them to fend for themselves in the face of real threats.

Running parallel to Cheryl’s story is that of the grieving friend, who recognizes Alcala from a police sketch connected to her friend’s murder. Her efforts to convince the police of his danger are met with skepticism, dismissiveness and outright disregard. This subplot deepens the film’s feminist critique, showing how institutional apathy toward women’s warnings and grief perpetuates cycles of violence. The emotional weight of her struggle shows a central theme of the film: women are often left to do the work of protecting each other when the systems designed to protect them fail. This combination of the disregard for Cheryl’s visible discomfort and Laura’s overlooked statement highlights the dangerous consequences of dismissing women’s intuition and testimony.

Set in the 1970s, the film’s feminist critique functions as both a period piece and a commentary on enduring societal issues. The game-show format becomes a powerful metaphor for the exploitation of women, reducing them to objects of entertainment while obscuring their humanity. The fact that Alcala, despite his suspicious behavior and criminal history, was selected as a contestant points to a culture that prioritizes male charisma over women’s safety.

Kendrick’s portrayal of Cheryl is layered and compelling, presenting her as both vulnerable and resilient. Laura, though a secondary character, is equally compelling, serving as a voice of moral clarity. Her persistence in seeking justice, even in the face of systemic indifference, embodies a quiet heroism that contrasts the institutional failures around her.

Visually, the film is sharp and purposeful. Zach Kuperstein’s cinematography contrasts the artificial glow of the game show set with the grim realities of Alcala’s private life, driving home the film’s central theme: the dangerous facade of performative masculinity. The bright, polished world of entertainment serves as a chilling contrast to the darkness lurking beneath Alcala’s charming exterior.

The film ends on a haunting note, as on-screen text reveals the staggering scope of Alcala’s crimes. Over the years, he is believed to have murdered at least 130 women, many of whose cases remain unresolved. This statistic leaves the audience grappling with the enormity of the loss and the systemic failures that allowed Alcala to escape justice for so long. The stark numbers serve as a chilling reminder of the real lives lost and the deep societal complicity in his crimes.

Ultimately, “Woman of the Hour” is a powerful, unsettling film that interrogates how society facilitates gendered violence while silencing women’s voices. Kendrick’s approach to true crime is notably diligent; in interviews, she revealed that she felt “gross” profiting from the project and chose to donate her earnings to charity. This stands in contrast to the trend of sensationalizing true crime for entertainment, a critique often leveled at productions like the Netflix “DAHMER” (2022) series and recent dramatizations of the Menendez brothers’ case.

With “Woman of the Hour,” Kendrick establishes herself as a director unafraid to confront uncomfortable truths, offering a deeply feminist perspective on a story that continues to resonate in today’s cultural landscape.

![At the pepfest on Feb. 13 the Winterfest Royalty nominees were introduced. There were two girls and two boys candidates from each grade. Royalty included Prince Axel Calderon (11), Jacob Miller (12), Princess Maya Fuller (11), Brecken Wacholz (10), Ethan Brownlee (9), Lord Given Saw (9), Lilly Elmer (9), Angela Buansombat (10), Queen Jenna Balfe (12), Hanna Austinson (11), Raegan Broskoff (8), Duchess Evalyn Holcomb (10), Jordyn Earl (8), and Lady Leighton Brenegan (9). Not pictured include: King Kaiden Baldwin-Rutherford (12), Piper Aanes (12), Blair Blake (11), Duke Kuol Duol (10), Thoo Kah (8) and Aidric Calderon (8). Student council member and Junior Prince Axel Calderon said, “It [the nomination] means that I’m kind of a student leader. I hopefully show younger kids what it means to be a part of the student council and lead the school.”](https://www.ahlahasa.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/front-page-1200x800.jpeg)